Political influence leaves fragile banks struggling to stay afloat

One of the most troubled is Padma Bank, formerly Farmers Bank

Mousumi Islam, Dhaka

Published: 13 Apr 2025

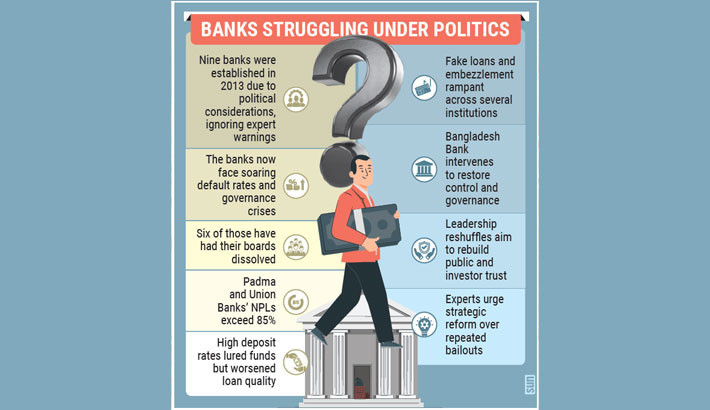

Twelve years after being established to boost economic growth, nine fourth-generation banks in the country are now facing an alarming financial crisis, overwhelmed by corruption scandals, mismanagement, and ballooning non-performing loans (NPLs) that have left many teetering on the brink of collapse.

Most of these banks, set up in 2013, were greenlit not because of market need, but due to political considerations during the Sheikh Hasina-led government.

Despite opposition from financial experts, the authorities went ahead and approved licences for Padma (formerly Farmers Bank), Global Islami Bank (formerly NRB Global Bank), NRB Commercial Bank, NRB Bank, Union Bank, Meghna Bank, Modhumoti Bank, South Bangla Agriculture and Commerce (SBAC) Bank, and Midland Bank.

Today, six of the nine banks have had their boards dissolved by the Bangladesh Bank amid efforts to clean up governance and stop further financial deterioration. In some cases, NPLs have soared as high as 88%.

“The pressure to withdraw small deposits has eased a bit, but the pressure from corporate clients still remains,” said Mohammed Nurul Amin, the newly appointed chairman of Global Islami Bank.

“We are trying to handle it in various ways. A forensic investigation is currently underway, and the true picture will emerge after the investigation is completed.”

These banks had initially attracted depositors by offering unusually high interest rates – often higher than those of more established institutions. It worked for a while, but it also encouraged aggressive lending practices and opened the doors to irregularities.

One of the most troubled is Padma Bank, formerly Farmers Bank.

It quickly fell into disarray after its launch, under the leadership of then home minister Dr Mohiuddin Khan Alamgir. Poor governance and political interference led to severe mismanagement. By 2017, the board was dissolved.

In 2018, Chowdhury Nafeez Sarafat, chairman of RACE Asset Management, took charge and the bank was rebranded as Padma Bank in 2019. However, it continued to struggle with its tainted reputation. Sarafat eventually resigned in January 2024.

Despite receiving capital support from four state-owned banks and the Investment Corporation of Bangladesh, Padma Bank had disbursed Tk5,628 crore in loans by the end of 2024. Of this, Tk4,870 crore – over 86% – has turned into bad loans.

The bank has not set aside a single taka in loan provisions and is now struggling to pay staff salaries. It has asked Bangladesh Bank for a Tk5,000 crore bailout to stay afloat.

Kazi Md Talha, CEO of Padma Bank, admitted, “The bank’s financial health worsened after the merger announcement by the government at that time. We always kept discussions open with the central bank. We are trying our best to recover.”

Union Bank is another grim story.

It was established under the leadership of Shahidul Alam, brother of the S Alam Group chairman, giving the business conglomerate control over the bank’s affairs. Over the years, several top executives at the bank were found to be closely connected to the group.

Under their leadership, the bank focused on collecting large deposits – mainly from government sources – and disbursed massive loans to companies, many of which later turned out to be fake.

By 2021, an audit revealed that 95% of the bank’s loans had become non-performing. Over 300 companies had received loans, most of them paper entities. Fake loans were even created for political candidates in exchange for votes.

A shocking scandal surfaced at Union Bank’s Gulshan branch in 2021, when Tk19 crore was discovered missing from the vault. Despite the evidence, no legal steps were taken.

Leadership changes followed in August 2024, and Md Fariduddin Ahmed, a former MD of Exim Bank, was brought in as chairman in a desperate bid to stabilise the bank.

By the end of 2024, Union Bank’s loan portfolio reached Tk28,230 crore – of which Tk24,835 crore, or 88%, had defaulted.

Meanwhile, NRB Global Bank, which rebranded as Global Islami Bank in 2021 after its MD PK Halder was caught embezzling vast sums from non-bank financial institutions, has not fared much better.

As of December 2024, the bank had issued Tk14,397 crore in loans, with Tk4,443 crore or 31% classified as NPLs. A staggering 80% of its loans went to the S Alam Group, raising serious questions about governance and risk oversight.

Three more banks – Meghna, NRB, and NRB Commercial – had their boards dissolved by Bangladesh Bank after their top executives fled on 5 August 2024.

The central bank said these moves were necessary to “restore good governance” and free the banks from political influence.

At Meghna Bank, former chairman HN Ashequr Rahman, a senior Awami League leader, had long dominated the board, which also included members of former land minister Saifuzzaman Chowdhury’s family.

The bank struggled with internal management issues, prompting Bangladesh Bank to step in. Uzma Chowdhury has since been appointed as the new chairperson.

Meghna Bank’s financials are less worrying than others, with Tk6,745 crore in total loans and a default rate of just 3.78%.

NRB Bank reported NPLs of 6.86% (Tk459 crore) out of Tk6,695 crore in loans.

Iqbal Ahmed OBE, the newly appointed director of NRB Bank and also its founding chairman, told the Daily Sun, “Establishing good governance in the bank is the main task. The Governor has also emphasised that. We’ve discussed in the board meeting how to restore NRB Bank to its previous state.”

Other banks like Modhumoti, Midland, and SBAC have managed to keep their default rates relatively low: Modhumoti at 1.85% (Tk122 crore), Midland at 3.78% (Tk239 crore), and SBAC at 6.81% (Tk599 crore).

Ali Hossain Prodhania, newly appointed chairman of NRBC Bank, said: “I have just joined a few days ago. I’m trying to get a basic understanding of the bank; I’m keeping it under observation.”

Experts are now urging the government and central bank to rethink their approach.

Dr Mustafa K Mujeri, executive director of the Institute for Inclusive Finance and Development and former chief economist at the Bangladesh Bank, said, “Weak banks cannot be saved by giving money day after day. Proper plans must be made to sustain them. Saving banks by lending money is not a solution. Now it’s time to take a master plan to rescue these banks.”

One common feature across the troubled banks has been their use of high deposit interest rates to attract funds.

According to Bangladesh Bank data, as of February 2025, Meghna Bank offered the highest rate on fixed deposits under one year at 10.8%, followed closely by Global Islami (10.75%), Midland (10.69%), Modhumoti (10.02%), and Union (9.89%).

For fixed deposits over a year, Global Islami topped the chart again with 11.60%, followed by NRB (11.50%), Meghna (11.35%), and Union (11.07%). Even Padma Bank, despite its poor performance, continued to offer 9.65% for long-term deposits.

The high rates reflect a desperate attempt to keep cash flowing, but with no clear path to reform or accountability, the future of these banks – and the depositors who still trust them – remains uncertain.

Political influence leaves fragile banks struggling to stay afloat

Mousumi Islam, Dhaka

Twelve years after being established to boost economic growth, nine fourth-generation banks in the country are now facing an alarming financial crisis, overwhelmed by corruption scandals, mismanagement, and ballooning non-performing loans (NPLs) that have left many teetering on the brink of collapse.

Most of these banks, set up in 2013, were greenlit not because of market need, but due to political considerations during the Sheikh Hasina-led government.

Despite opposition from financial experts, the authorities went ahead and approved licences for Padma (formerly Farmers Bank), Global Islami Bank (formerly NRB Global Bank), NRB Commercial Bank, NRB Bank, Union Bank, Meghna Bank, Modhumoti Bank, South Bangla Agriculture and Commerce (SBAC) Bank, and Midland Bank.

Today, six of the nine banks have had their boards dissolved by the Bangladesh Bank amid efforts to clean up governance and stop further financial deterioration. In some cases, NPLs have soared as high as 88%.

“The pressure to withdraw small deposits has eased a bit, but the pressure from corporate clients still remains,” said Mohammed Nurul Amin, the newly appointed chairman of Global Islami Bank.

“We are trying to handle it in various ways. A forensic investigation is currently underway, and the true picture will emerge after the investigation is completed.”

These banks had initially attracted depositors by offering unusually high interest rates – often higher than those of more established institutions. It worked for a while, but it also encouraged aggressive lending practices and opened the doors to irregularities.

One of the most troubled is Padma Bank, formerly Farmers Bank.

It quickly fell into disarray after its launch, under the leadership of then home minister Dr Mohiuddin Khan Alamgir. Poor governance and political interference led to severe mismanagement. By 2017, the board was dissolved.

In 2018, Chowdhury Nafeez Sarafat, chairman of RACE Asset Management, took charge and the bank was rebranded as Padma Bank in 2019. However, it continued to struggle with its tainted reputation. Sarafat eventually resigned in January 2024.

Despite receiving capital support from four state-owned banks and the Investment Corporation of Bangladesh, Padma Bank had disbursed Tk5,628 crore in loans by the end of 2024. Of this, Tk4,870 crore – over 86% – has turned into bad loans.

The bank has not set aside a single taka in loan provisions and is now struggling to pay staff salaries. It has asked Bangladesh Bank for a Tk5,000 crore bailout to stay afloat.

Kazi Md Talha, CEO of Padma Bank, admitted, “The bank’s financial health worsened after the merger announcement by the government at that time. We always kept discussions open with the central bank. We are trying our best to recover.”

Union Bank is another grim story.

It was established under the leadership of Shahidul Alam, brother of the S Alam Group chairman, giving the business conglomerate control over the bank’s affairs. Over the years, several top executives at the bank were found to be closely connected to the group.

Under their leadership, the bank focused on collecting large deposits – mainly from government sources – and disbursed massive loans to companies, many of which later turned out to be fake.

By 2021, an audit revealed that 95% of the bank’s loans had become non-performing. Over 300 companies had received loans, most of them paper entities. Fake loans were even created for political candidates in exchange for votes.

A shocking scandal surfaced at Union Bank’s Gulshan branch in 2021, when Tk19 crore was discovered missing from the vault. Despite the evidence, no legal steps were taken.

Leadership changes followed in August 2024, and Md Fariduddin Ahmed, a former MD of Exim Bank, was brought in as chairman in a desperate bid to stabilise the bank.

By the end of 2024, Union Bank’s loan portfolio reached Tk28,230 crore – of which Tk24,835 crore, or 88%, had defaulted.

Meanwhile, NRB Global Bank, which rebranded as Global Islami Bank in 2021 after its MD PK Halder was caught embezzling vast sums from non-bank financial institutions, has not fared much better.

As of December 2024, the bank had issued Tk14,397 crore in loans, with Tk4,443 crore or 31% classified as NPLs. A staggering 80% of its loans went to the S Alam Group, raising serious questions about governance and risk oversight.

Three more banks – Meghna, NRB, and NRB Commercial – had their boards dissolved by Bangladesh Bank after their top executives fled on 5 August 2024.

The central bank said these moves were necessary to “restore good governance” and free the banks from political influence.

At Meghna Bank, former chairman HN Ashequr Rahman, a senior Awami League leader, had long dominated the board, which also included members of former land minister Saifuzzaman Chowdhury’s family.

The bank struggled with internal management issues, prompting Bangladesh Bank to step in. Uzma Chowdhury has since been appointed as the new chairperson.

Meghna Bank’s financials are less worrying than others, with Tk6,745 crore in total loans and a default rate of just 3.78%.

NRB Bank reported NPLs of 6.86% (Tk459 crore) out of Tk6,695 crore in loans.

Iqbal Ahmed OBE, the newly appointed director of NRB Bank and also its founding chairman, told the Daily Sun, “Establishing good governance in the bank is the main task. The Governor has also emphasised that. We’ve discussed in the board meeting how to restore NRB Bank to its previous state.”

Other banks like Modhumoti, Midland, and SBAC have managed to keep their default rates relatively low: Modhumoti at 1.85% (Tk122 crore), Midland at 3.78% (Tk239 crore), and SBAC at 6.81% (Tk599 crore).

Ali Hossain Prodhania, newly appointed chairman of NRBC Bank, said: “I have just joined a few days ago. I’m trying to get a basic understanding of the bank; I’m keeping it under observation.”

Experts are now urging the government and central bank to rethink their approach.

Dr Mustafa K Mujeri, executive director of the Institute for Inclusive Finance and Development and former chief economist at the Bangladesh Bank, said, “Weak banks cannot be saved by giving money day after day. Proper plans must be made to sustain them. Saving banks by lending money is not a solution. Now it’s time to take a master plan to rescue these banks.”

One common feature across the troubled banks has been their use of high deposit interest rates to attract funds.

According to Bangladesh Bank data, as of February 2025, Meghna Bank offered the highest rate on fixed deposits under one year at 10.8%, followed closely by Global Islami (10.75%), Midland (10.69%), Modhumoti (10.02%), and Union (9.89%).

For fixed deposits over a year, Global Islami topped the chart again with 11.60%, followed by NRB (11.50%), Meghna (11.35%), and Union (11.07%). Even Padma Bank, despite its poor performance, continued to offer 9.65% for long-term deposits.

The high rates reflect a desperate attempt to keep cash flowing, but with no clear path to reform or accountability, the future of these banks – and the depositors who still trust them – remains uncertain.