The Puranas are a class of literary texts, all written in Sanskrit verse, whose composition dates from the 4thcentury BCE to about 1,000 A.D. The word “Purana” means “old”, and generally they are considered as coming in the chronological aftermath of the epics, though sometimes the Mahabharata, which is generally classified as a work of itihas (history), is also referred to as a purana. Some scholars, such as van Buitenen, are inclined to view the Puranas as beginning around the time that the composition of the Mahabharata came to a close, that is about 300 A.D. Certainly, in its final form the Mahabharata shows puranic features, and the Harivamsa, which is an appendix to the Mahabharata where the life of Krishna or Hari is treated at some length, has sometimes been seen as a purana.

The special subject of the puranas is the powers and works of the gods. An ancient Sanskrit lexicographer named Amarasinha defined purana in his writing as having five characteristic topics, or pancalaksana. Puranas talk about the creation of the universe, its destruction and renovation, the genealogy of gods and patriarchs, the reigns of the Manus, forming the periods called Manwantaras and the history of the Solar and Lunar races of kings. No single purana can be described as exhibiting in fine (or even coarse) detail all five of these distinguishing traits, but sometimes the Vishnu Purana is thought to most closely resemble the traditional definition. Around the time when the puranas first began to be composed, the belief in particular deities had become established as one of the principal marks of the Hindu faith, and to some degree the puranas can be described as a form of sectarian literature. Some puranas exhibit devotion to Shiva; in others, the devotion to Vishnu predominates.

There are eighteen major puranas, as well as a similar number of minor or subordinate puranas. One method of the classification of puranas deploys the traditional tripartite division of the gunas or qualities which tend toward purity (sattva), impurity or ignorance (tamas), and passion (rajas). Thus, there are those puranas where the quality of sattva is said to predominate, and these are six in number: Vishnu; Narada; Bhagavata; Garuda; Padma; and Varaha. According to another scheme of classification, these are also the puranas in which Vishnu appears as the Supreme Being. A second set of puranas, also six in number, are described as exhibiting qualities of ignorance or impurity (tamas), and in these Shiva is the God to whom devotion is rendered: Matsya; Kurma; Linga; Shiva; Skanda; and Agni. In the third set of six puranas, the quality of rajas or blind passion supposedly prevails: Brahma; Bramanda; Brahmavaivarta; Markandeya; Bhavishya; and Vamana. The list of eighteen is sometimes enlarged to twenty, to include the Vayu Purana and the Harivamsa.

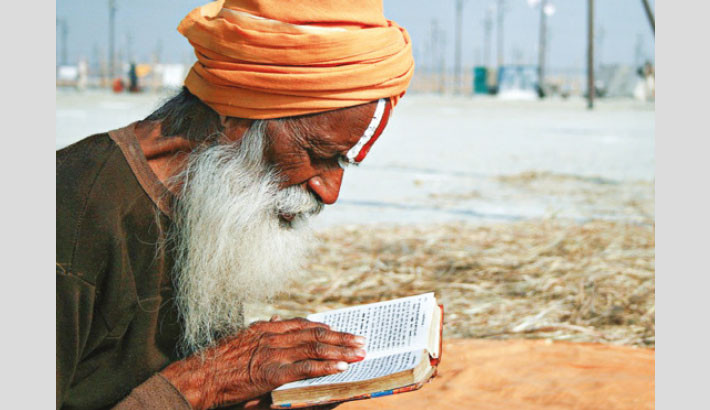

Though all the Puranas have been translated into major Indian languages as well as English, only a few of them, principally the Vishnu Purana and the Bhagavatam, can safely be described as being widely known. Nonetheless, the stories told in the Puranas are part of the common currency, and in this respect the Puranas can rightfully be spoken of as the scriptures of popular Hinduism.

The Puranas are works that most eminently represent the deep mythic structuring of Indian civilisation, and they are properly viewed as expanding upon, modifying, and transforming the orthodox Brahminism of the Vedas, principally by the introduction of the idea of bhakti or devotion. It is the Puranas which, it is no exaggeration to say, assisted in the transition from Brahminism to Hinduism, particularly a Hinduism that was more receptive to folk elements, popular forms of devotion and worship, and everyday arts, crafts, and sciences.

The Puranas carry stories about the gods who had become the objects of people’s devotion, as well as about the modes of worship of these gods. Besides, the Puranas speak of the battle between the devas and the asuras, and one can read the narratives as allegorical accounts of the struggle between the forces of ‘light’ and ‘darkness’ in one's inner self. The Puranas delineate the religious obligations by which each person is bound, and as such those are guides to dharmic living. Though the Puranas are a vast repository of Hindu lore, religious practices — yoga, vows, puja, prayers, sacrifices — and everyday customs, they are not without a sense of humour and irony, and they complement the metaphysical austerity of the Upanishads, the magical and sacrificial lore of the Atharva Veda, and the sacerdotal orthodoxy of the Rig Veda.

_________________________

Courtesy: southasia.ucla.edu