Pranto Chatterjee

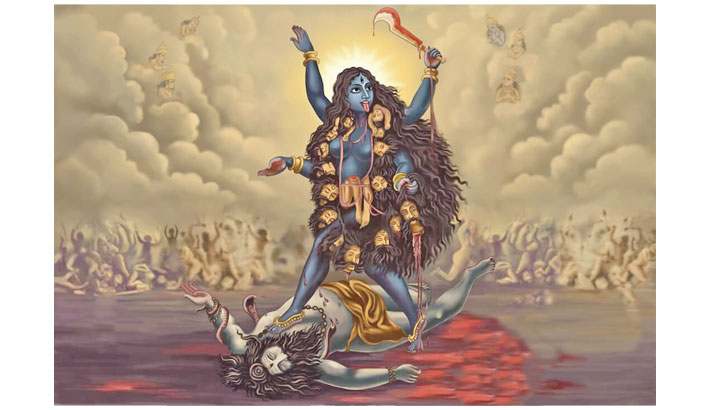

There is something primal about darkness. The moment the light flickers out, our heartbeat changes, imagination runs wild, and our sense of safety crumbles. Humanity has long associated darkness with fear, danger, and the unknown. And it is in this very darkness that Kali, the most misunderstood goddess of Hinduism, resides. She stands with wild hair, blood-red tongue, a garland of skulls, and a skirt of severed arms. To the casual onlooker, especially one unfamiliar with Indian philosophy, she appears monstrous. But the irony is that Kali, often painted as terrifying, is one of the most profound embodiments of love, protection, and liberation. The problem lies not in Kali herself but in our fear of darkness and our inability to embrace what she represents.

Kali is not one-dimensional. Hindu texts recognise multiple forms of her: Shyama Kali, Guhya Kali, Dakshina Kali, Smashana Kali, Bhadra Kali, Chamunda, and even the nurturing Annapurna. Each carries a symbolic lesson. Dakshina Kali, often worshiped in Bengal, is compassionate and motherly, standing with one foot on Shiva, offering boons to her devotees. Smashana Kali, the cremation-ground goddess, teaches the truth of impermanence and the futility of clinging to possessions. Bhadra Kali embodies ferocity against injustice, protecting the righteous while destroying evil. In every form, one truth shines through: Kali is not to be feared but understood. She terrifies us so that we confront our own fears, illusions and ego.

Much of the fear around Kali stems from colonial narratives. When the British encountered her worship in Bengal, they were horrified. They could not comprehend a mother goddess garlanded with skulls and standing in cremation grounds. Their Victorian worldview had no place for a deity symbolising both death and love. This misunderstanding fuelled orientalist writings, where Kali was painted as savage and barbaric. The infamous tales of the “Thuggees” amplified this fear. While criminal bands did exist, the British exaggerated them to demonise Kali and justify colonial control. The irony is that the very image that scared the colonisers gave strength to the colonised. Kali was invoked in revolutionary songs and battle cries of India’s freedom fighters as a symbol of fearlessness against tyranny.

Why do we misunderstand Kali? Because we fear what we do not know. Darkness is frightening not because of what it is but because we cannot see. Similarly, Kali represents the unknown aspects of existence—death, time, and dissolution of the ego. Most resist these realities, clinging to identities, possessions, and victories, believing them permanent. Kali shatters this illusion. Her garland of skulls is not a celebration of death but a reminder that pride is temporary. Her skirt of arms teaches that actions, once done, detach from us. Her tongue, stretched wide, exposes raw truth, stripping away pretences.

Kali’s fearsome imagery serves a paradoxical purpose. By appearing terrifying, she forces us to confront the very things we avoid. In psychological terms, she embodies the shadow—those hidden parts of our psyche we repress. Carl Jung argued that self-realisation comes from embracing, not denying, our shadow. Kali is the archetype of this truth. She tells us that liberation lies not in running from fear but in walking through it.

Kali’s love is not sentimental. It is transformative. She saves us not by sheltering us from reality but by throwing us into it. She destroys our ego, the greatest obstacle to freedom. In Hindu philosophy, the ego—the Ahamkara—is the false identification with body and mind. It convinces us that we are separate and fragile. Kali stands upon Shiva not to dominate him but to symbolise the triumph of cosmic power over inert consciousness.

For society, Kali’s presence is invaluable. She is the goddess of revolutions, the force that refuses to let corruption or injustice stand unchallenged. Many reformers and freedom fighters saw her as their guiding spirit. In Bengal’s imagination, she is not merely a goddess in the temple but a symbol of resilience in the household, giving people courage to face extraordinary challenges. When women were confined to silence, Kali’s image gave them voice. When people were trapped in colonial subjugation, Kali gave them defiance. Today, when society is shackled by materialism and fear of change, Kali’s lesson is more relevant than ever.

It is important to know that Kali worship is not regressive or violent. Rather, it is deeply philosophical and constructive. Rituals often take place at night, symbolising the embrace of darkness. They happen in cremation grounds, symbolising fearlessness in the face of mortality. These practices are not about bloodlust but dissolving barriers of the mind.

In conclusion it can be said that Kali’s lesson is timeless. Darkness is not the enemy. The real enemy is ignorance—the refusal to look within, the refusal to let go of ego. Kali is not the goddess of terror. She is the goddess of truth. And truth, as every society eventually learns, is the most loving force of all.

______________________________________

The writer is an Electrical Engineer and is currently pursuing an MSc in Autonomous Vehicle Engineering at the University of Naples Federico II in Italy