World prices down, local costs up: Why inflation stays high in Bangladesh

Despite easing global supply pressures and cheaper commodities abroad, local markets show little sign of relief

As the world enjoys a wave of price relief, Bangladesh remains trapped in a stubborn cycle of high inflation.

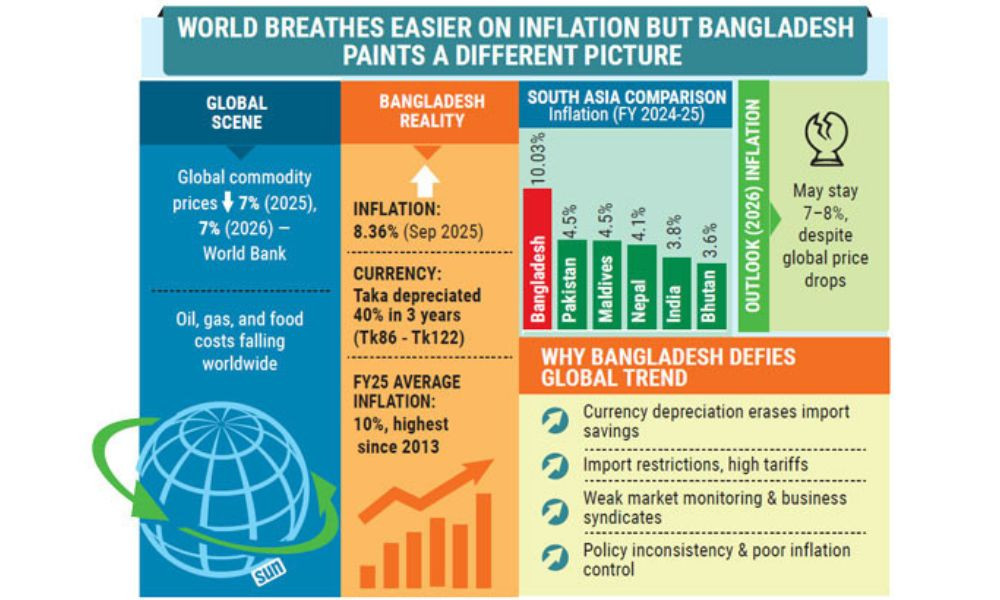

Across global markets, the prices of fuel, food, and raw materials are falling. The World Bank projects a 7% drop this year and another 7% in 2026. Yet, Bangladeshi consumers continue to pay more for daily essentials.

Despite easing global supply pressures and cheaper commodities abroad, local markets show little sign of relief. Economists cite a mix of currency depreciation, weak market governance, import restrictions, and policy missteps as key reasons global deflation has failed to reach Bangladeshi households.

The World Bank’s Commodity Markets Outlook (October 2025) forecasts a 7% global price decline in both 2025 and 2026. Yet Bangladesh continues to struggle with elevated inflation, recording 8.36% in September 2025, among the highest in South Asia.

In the 2024-25 fiscal year, when Bangladesh’s average inflation reached 10%, the highest since FY13, its closest regional peers were the Maldives and Pakistan, both around 4.5%, according to the Asian Development Bank’s Asian Development Outlook (September 2025). Nepal’s inflation stood at 4.1%, while Bhutan and India remained significantly lower.

The currency effect: Taka’s fall offsets global gains

The Bangladeshi taka has lost more than 40% of its value in just three years, sliding from Tk86 per dollar to around Tk122. This steep depreciation means importers now pay much more in local currency, even as global commodity prices fall.

“Due to the weaker taka, the fall in global prices has not translated into cheaper domestic goods,” said Prof Mustafizur Rahman, distinguished fellow at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD). “The benefits of deflation abroad are being neutralised by currency depreciation at home.”

High import tariffs, complex tax structures, and inefficient market management continue to push up the cost of essentials like food grains, fuel, and edible oils.

Economists point to poor demand forecasting, delayed import decisions, and weak market coordination as aggravating factors that have allowed speculative behaviour and supply disruptions to persist.

Domestic transport and logistics costs have not fallen in line with global trends due to high local fuel and electricity prices.

At the same time, entrenched business syndicates have limited competition and allowed artificial price manipulation.

Even when wholesale prices decline, retail prices often remain high, a “price transmission gap” driven by profit-seeking intermediaries and lax enforcement.

Speaking to the Daily Sun, Dr Zahid Hussain, former lead economist of the World Bank’s Dhaka Office, offered a sharp critique of Bangladesh’s inflation management.

“Our food inflation started rising right after COVID-19, and the Ukraine war added further pressure. Later, when global inflation began to decline, Bangladesh couldn’t bring it down accordingly,” he said.

“The main reason was policy failure – we couldn’t implement our budgetary initiatives effectively, which weakened our inflation control mechanisms.”

Dr Hussain noted that restrictive import policies during the foreign currency shortage allowed local businesses to exploit reduced competition.

“After 5 August, when political changes occurred, there was some temporary stabilisation and inflation fell from double digits to single digits,” he added.

Despite stronger remittance inflows, investment remained weak due to political uncertainty.

Citing the IMF’s 2023 report, Dr Hussain said, “Around 50% of Bangladesh’s inflation rise was due to the appreciation of the US dollar. We had a chance to ease pressure by releasing more foreign currency between May and August 2025, but Bangladesh Bank instead purchased nearly US$2 billion, pushing the dollar price even higher.”

He warned that the failure to rein in syndicates and ensure competitive markets has kept inflation entrenched.

“Whenever the price of one product falls, another rises. The main reason is market syndicates and weak monitoring. Temporary fines and raids don’t solve the problem. Unscrupulous businessmen keep raising prices because new competitors aren’t emerging. The market remains captive to a few powerful groups.”

Dr Hussain also cautioned that liquidity injections into weak banks and pre-election spending could fuel additional price pressures.

“Globally, oil, gas, and other commodity prices are falling – yet in Bangladesh, prices are still rising. This is the result of poor monetary discipline and policy inconsistency.”

The broader macroeconomic picture

Despite modest wage growth – 8.1% in FY2025, up from 7.5% in FY24 – real incomes continue to decline, as inflation remains above 10%.

Energy and fertiliser prices, which are expected to drop globally by 10%-12% in 2026, remain high in Bangladesh due to exchange rate pressures and import restrictions.

Meanwhile, private investment is subdued amid policy uncertainty, high borrowing costs, and a fragile financial sector. With global prices expected to fall further, Bangladesh could, in theory, benefit from cheaper imports.

But without stronger policy coordination, better exchange rate management, and improved market governance, inflation may remain stuck around 7%-8% in 2026, well above the regional average.

As Dr Zahid Hussain summed up, “We never managed to keep inflation down permanently because the system itself allows price manipulation. Without strong market monitoring, fair competition, and credible macroeconomic management, inflation will remain a chronic problem, not a temporary one.”

The reporter can be reached at: [email protected]

Edited by: Anayetur Rahaman