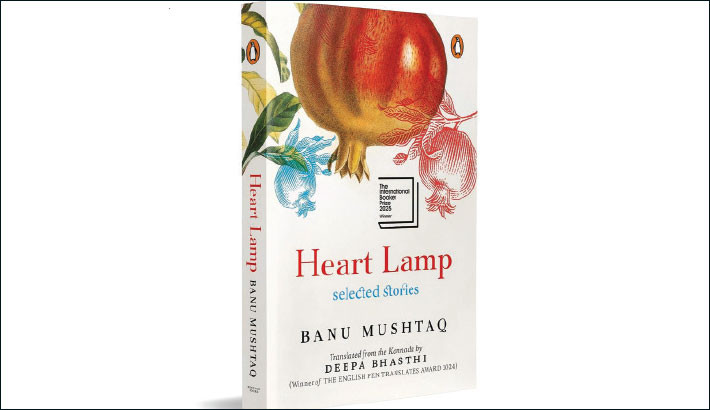

Heart Lamp by Banu Mushtaq, translated by Deepa Bhasthi, is a collection of short stories that captures the everyday trials and tribulations of Muslim women with candour. This book has won the International Booker Prize 2025. Mushtaq’s Heart Lamp presents 12 short stories with themes comprising a vast oeuvre, traverse religion, patriarchy, oppression, gender inequality and violence, vividly capturing the everyday trials and tribulations of Muslim women in Karnataka and South India. But they are also universal; the stories and characters could be found any-where in India or the world.

Religious and social binds

In the eponymous story ‘Heart Lamp’, Mehrun, a mother of three, decides to end her life after her husband acquires a second wife. She has endured enough and the “lamp in Mehrun’s heart had been extinguished a long time ago”. She decides to drench herself in kerosene and is ready to light a matchstick when her daughter Salma rushes to her mother with her baby sister and begs her not to make them orphans.

Religion and societal structures are unjust to Muslim women; the author critiques and exposes the hypocrisy of men, including the Muttawalli Saheb (the local religious custodian). The inapt machismo and man’s role of “provider” is apparent from the opening story ‘Stone Slabs for Shaista Mahal’.

There are women who are strong and take matters into their own hands. In ‘Black Cobras’, a poor mother, Aashraf, turns to the Muttawalli for succour after her errant husband abandons her and their children for a younger wife, but to no avail. While Aashraf remains helpless, the women in the village, like cobras, spew venom on the Muttawalli.

When he is walking home, a woman flings a stone towards him shouting, “A dog, just a dog.” Another yells: “Nothing good will come your way… may black cobras coil themselves around you.” When the Muttawalli reaches home, his wife delivers the coup de grace.

Question of agency

Faith and inhumanity form the crux of ‘Red Lungi’. Razia, who has to manage 18 children dur-ing the summer vacations, decides the only way to ensure peace in the house is to have the boys circumcised. Even the poor families in the village are told to bring their sons for circumcision at a planned mass event.

Strangely, the boys from poor families who were circumcised in the traditional, old-fashioned way, recover quickly, while those from Razia’s family who were anaesthetised take a longer time. “If there are people to help the rich, the poor have God,” grumbles Razia.

Men are also prone to suffering; like Yusuf, who is torn between his widowed mother and a bel-ligerent wife in ‘A Decision of the Heart’. Yusuf decides to get his 50-year-old mother married to spite his wife.

An amusing story ‘The Arabic Teacher and Gobi Manchuri’ talks about a young tutor who holds Arabic classes for girls with the aim of finding a suitable bride for himself, someone who must know how to make his favourite dish. He succeeds in finding his ‘dream girl’ but life after mar-riage is something else.

The suffering of women and their lack of, or limited, agency coupled with the monotonous theme of the stories do make the reader feel dreary; equally, it engenders admiration for the au-thor and her ability to write realistic stories, rendered with profound observations, feeling, irony and dry humour.

Nod to regional literature

I cannot end without highlighting what the Booker judges said about the book: “... At its heart, Heart Lamp returns us to the true, great pleasures of reading: solid storytelling, unforgettable characters, vivid dialogue, tensions simmering under the surface, and a surprise at each turn.”

_________________________________

The reviewer is a Bengaluru-based

independent journalist.

Courtesy: thehindu.com