Bahauddin Golap

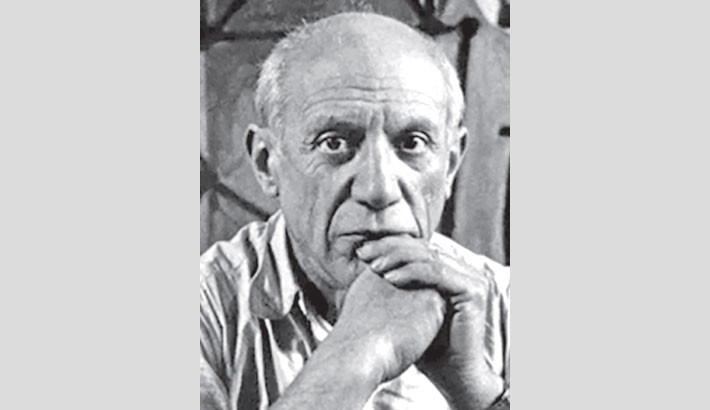

As the dawn of the twentieth century bled across Europe—a continent convulsing with the sharp edges of a new age—art, politics, and society whirled in a fierce, uneasy vortex. The roar of imperialism, the relentless mechanisms of the Industrial Revolution, the delirium of technology, and the spreading shadow of war formed a contradictory epoch. Into this tumultuous core, on an autumn morning, 25 October, 1881, a child was born in Málaga, Spain. He was a child whose brushstrokes would not merely embody colour, but also capture the very soul of humanity. His name was Pablo Picasso—the man who did not just paint pictures, but re-authored the very grammar of art for humankind.

Picasso’s journey began with the emulation of beauty, yet he swiftly realised that art was not reality’s follower, but its revolutionary alternative. While Europe remained tethered to the Renaissance's enduring echo, Picasso unveiled Les Demoiselles d’Avignon—a canvas that struck at the heart of conventional beauty. Bodies were fractured, faces distorted, poses jarring; yet, from that very distortion, the genuine complexity of the human spirit seemed to emerge. This picture birthed Cubism—a radical fracturing of reality, reassembled into a new whole, where one gaze seemed to beget another within the frame.

His contemporary world was a chasm of conflict and politics. The devastation of the First World War, the rise of fascism, the agony of the Spanish Civil War—all violently stirred Picasso’s conscience. For him, art was never mere ornamentation; it was a moral arsenal. This conviction culminated in Guernica—a protest against the global conscience. The monochrome tapestry of black, white, and grey offered no embellishment, only an inexorable scream. The bovine eye, the broken sword, the inert body of the child—together, they stripped the mask of war bare before humanity. He asserted, “Painting is not made to decorate apartments; it is an instrument of war against brutality.” From Vietnam to Gaza, wherever humanity's blood is spilled, that stark black-and-white image resurrects, reminding us, across time, of art’s moral imperative.

In the same era, across Europe, Henri Matisse sought a dance of peace within colour, Dalí sculpted the art of delusion from the melting expanse of dreams and Mondrian pursued spiritual stability through geometric lines. But Picasso occupied a different pole. There was no placidity in his work, only intense, visceral life. Where Matisse found repose, Picasso rendered colour into a question. He saw rhythm within the chaos and the potential for creation within destruction. His canvas proclaimed that truth, not beauty, was art's ultimate sanctuary.

Through various seasons of his life, Picasso relentlessly reinvented himself. His Blue Period became an icon of azure melancholia—the lonely cry of an orphaned world. In The Old Guitarist, the emaciated figure's music echoes the void of existence. This gave way to the Rose Period—a tender romanticism revealing the poignant beauty of human life behind the circus's cheerful façade. Then came Cubism, the full flowering of his artistic philosophy. Each phase was a diary of his soul, where every line was a sensation, every colour a philosophy.

The weight of age never arrested his hand, however. Until the day before his death, the brush was in his grasp, curiosity in his gaze. His final works present a synthesis of peace and sorrow—the silence of death intermingling with the rapture of creation. He understood that long after an artist perishes, their colour lives on in the human eye, their line endures upon the canvas of history.

In the trajectory of modernity, Picasso is an indelible symbol. He proved that art is not aloof from society, but its very conscience, the echo of its time. His creations embody both radical self-interrogation and fierce protest. Picasso’s canvas displays the fractured history, the isolation of humanity and within it, an astonishing pulse of life.

His influence has permeated the entirety of modern art. The Cubist premise—that reality is not monolithic but multi-layered—resonated through Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism and countless subsequent movements. His fascination with African mask art gave rise to the concept of “Primitivism” in global art, centring the aesthetic power of marginalised cultures. Through Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, he effectively reversed the colonial gaze—a concept that remains a foundational source for post-colonial art theory.

Picasso demonstrated that colour is not mere sight, but a state of being; the brush is not a tool, but a philosophical soul. He did not merely launch a revolution of colour; he instigated a revolution of vision. When we behold his canvases, we witness the autobiography of man hidden within the lines, the ineluctable melody of life awakened within the colour. He teaches us how to see, how to contemplate and above all, how to create in our own likeness.

As long as humans think, love, and dream, Pablo Picasso will endure—like colour, like light, like time itself. Every single one of his creations is proof that man may perish, but art never does.

______________________________

The writer is Deputy Registrar of University of Barishal.

He can be reached at : [email protected]